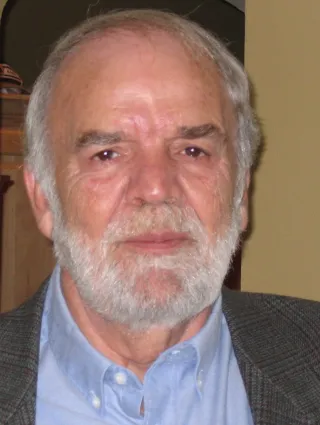

Tributes to Larry Jacoby

By Alan J. Lambert

Larry Jacoby was a cherished member of our department from 2000 to 2016. We were greatly saddened to hear of his passing on Friday, March 16th, from complications of pneumonia. His wife, Carole, was with him, along with their children, Derek and Karin, and his granddaughters.

In the field of psychology, we occasionally see someone develop a line of work which turns out to have a profound impact on their chosen sub-specialty. This might include, for example, a cognitive psychologist who exerts powerful influence on theory and research in cognitive science. Or a social psychologist who greatly impacts the direction of social psychology. Larry was initially trained as a cognitive scientist and, without question, his work had enormous impact on the ways that cognitive scientists think about topics central to their field, especially memory processes. However, Larry’s impact was far-reaching and extended to several other fields, such as social, personality, and developmental psychology. This includes, but is not limited to, his enormously influential work on automatic and controlled processes. A more detailed assessment of Larry’s scientific contributions can be found here.

Before turning to the wonderful tributes offered by Larry’s colleagues/students in the following sections, I would like to offer a few personal memories of my own.

During the sixteen years that he was at Washington University, I was able to see many sides of Larry, such as Larry, the brilliant scientist. I also co-taught a course on Social Cognition with Larry, and he was profoundly influential in the way that I came to think about research in that and other fields of study. Another face of Larry worth noting was his open praise of ideas and scientists he admired; for the ideas and scientists he wasn’t keen on, let’s just say that he didn’t mince words. Before embarking on a new research plan, I will sometimes think to myself, “What would Larry think of this?” This helped me be a more objective scientist in choosing when to stay the course or drop the new plan in favor of a more productive pathway. God knows, Larry knew a good idea when he saw one. In this, and in many other respects, Larry was special. He was unique. I shall miss you, my friend.

Keith Payne

University of North Carolina

Larry served as one of my primary mentors while I was a graduate student at Washington University. In this role, Larry was quick to share his brilliant perspective, but also patient enough to let a student catch up. I always felt that he was thinking three or four steps ahead, but he gave me the space to learn things for myself. His mentorship always came with a good dose of humor, sometimes with an edge to it. “The becoming famous overnight paper was always meant as a joke,” he once told me. “That’s why I put it in JPSP.” A wonderful part of being mentored by Larry was that he gave advice not just about the science but also about how to communicate ideas. He once told me, “A good paper has a little counting and a little story telling. You’ve got a lot of counting here. It’s time for a better story.” Then he gave rounds and rounds of feedback, until I got the story right. Larry always got the story right.

Dave Balota

Washington University

Larry Jacoby was a member of our department for nearly two decades before his retirement. His influence on our understanding of memory processes, and conscious and unconscious contributions to cognition cannot be overestimated.

A remarkable aspect of Larry’s elegant empirical work is that it often involved higher order complex designs to isolate targeted mechanisms. These novel designs yielded highly replicable results that Larry often extended to everyday cognition. He was always full of interesting research ideas, and happy to discuss them, which led to important contributions to many research programs in our department. Larry also loved to take on new hobbies even in later life (and of course discuss them), which involved such things as learning how to play the banjo, video games, bird watching, and golf. I miss our chats and evenings together. Unlike many academics, Larry's educational background did not include elite or ivy league institutions. He received his B.A. from Washburn University where he was proud of being a football lineman and met his wonderful lifelong partner, Carole. He then went on to graduate school at SIU at Carbondale. Possibly, this background contributed to the maverick style that Andy Yonelinas describes below.

Andy Yonelinas

U.C. Davis

As a student interviewing for graduate school, my first impression of Larry was that he had a passion for science that was absolutely infectious. During the interview he explained a new approach he was developing for mathematically separating different cognitive processes that involved what seemed like an impossibly complicated set of equations that he quickly scribbled onto a scrap of paper. Even though I had no idea (at the time) what those equations meant, it seemed like Larry was on to something important, and I felt I had no choice but to go along for the ride.

Larry’s lab was an exciting place, and I remember essentially living in the lab, only taking a break for an occasional camping trip, Wallyball game or a BBQ in Larry’s back yard. I loved every minute of it, and the bonds I formed with the other students and with Larry have led to some of my most cherished and lasting friendships.

One of the exciting things about working with Larry was that he was interested in integrating many different research domains including memory, perception, language, action, child development, aging, and social cognition. And this led his work to have a remarkably broad and lasting impact. Some years ago, James Neely published a rather nice paper that identified the most influential papers in cognitive psychology over the past half a century. He looked at citations rates for the 85,000 papers published in the top journals in our area and identified the top 500 best papers based on citation rates. Most scientists--if they are lucky--have one major hit in their career, and after that they head to the faculty club for a scotch. To have more than 4 citation classics in one’s career is really quite rare, and it is the sort of thing that indicates that your work has consistently had a pretty substantial impact on the field. If you look up Larry in that list, you will find that he has seven papers that fall into that citation classic list. He was one of a very small and select group of scientists to have done this.

Of course, citations are not the only measures of success in our business. However, they’re a pretty good start. And if you ask people in the field to describe Larry and his contribution to the literature you will hear a number of terms very consistently. For example, he is often described as a “maverick thinker”, and his work is often described as “blazing new trails” in the science. Personally, I think these cowboy-related images suit Larry well. Larry was certainly not afraid to very strong and controversial theoretical positions. I believe it’s fair to say that a number of scientific careers have been based largely on attempts to criticize some of Larry’s work. But more importantly I think, it’s also fair to say that many more careers were based on attempts to build on Larry’s work, and to extend it in new and productive ways.

Roddy Roediger

Washington University

Larry Jacoby was a self-made academic. After receiving an undergraduate degree at Washburn University, he attended Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. His training and early publications were on animal learning and conditioning, as for many of us. But he switched to cognitive psychology and his first job was at Iowa State where he began publishing interesting work. A sabbatical at McMaster University, with frequent travels to the University of Toronto, changed the trajectory of his career. McMaster hired him, and his career continued to blossom from collaborations with his students and especially with Fergus (Gus) Craik.

Larry Jacoby was a great psychologist. He pioneered novel theoretical ideas and clever experimental procedures. His results were typically beautiful and compelling. I have taught courses on Human Memory for 50 years, and I doubt that I ever taught a course since the mid-1970s without having at least several of Larry’s papers on the syllabus and, depending on the topic, sometimes many more.

The first time I heard Larry’s name was during a brown bag meeting in 1971 when I was in graduate school. Endel Tulving, who was then the editor of the Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, came into the room waving a paper. He said “I have never met this young man Larry Jacoby, but he just submitted a wonderful paper. I predict a bright future for him.” That prediction certainly came true.